The following personal account is presented in the form of a paper

written for presentation to The Rump Steak Club,

Savannah, GA, March 30, 1998,

and is reprinted here, in slightly

different form, with permission of the author.

Recorded Radio Transcript:

"MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY,

Witch Doctor 5 is down just to the west

of A Luoi, crashed in the trees, over..."

That’s the voice of Lt. Ralph E. (Butch) Elliott, III, whose Huey

helicopter has been downed by .51 caliber machine gun fire about 12

miles into Laos. It’s March 5, 1971. It’s a bad day to be flying.

Two days prior to that, on another bad day for flying, I was shot down

not far from Butch, lured into the wrong LZ (landing zone) by North

Vietnamese Regulars. They were listening on all our radio frequencies

and knew that I was looking for yellow smoke to identify the LZ. They

obliged and within seconds we were on the ground, making a hasty exit

from the Huey that had already started to burn.

Butch and I were part of an operation known as Lam Son 719, conducted

out of I Corps (the northern-most tactical operating area in South

Vietnam) by Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops with US air and fire support. The objective was to destroy enemy bases at Tchepone,

some 26 miles into Laos, and cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The operation

consisted of four phases, beginning in late January 1971 and concluding

rather abruptly in mid-March. No US ground forces were to cross the

border, but US aviation support, both helicopter and tactical air, were

committed and would be crucial to the success of the operation. The most

significant airmobile/air assault battle of the war was also the last

major offensive supported by US troops of the Vietnam War.

To support this operation, in the latter part of January 1971, our

assault helicopter company (AHC), the 174th, moved from its fire base in

southern I Corps to Quang Tri, about 25 miles south of the DMZ. Butch

was a maintenance officer, and I was the Company Executive Officer. As

such, I had the unenviable task of leading a convoy north up Route 1. We

left our fire base at Duc Pho early one afternoon, drove to Chu Lai

where we were told our ultimate destination, then continued driving

north through the night, arriving about mid-afternoon the next day in

Quang Tri, a total distance of about 175 miles.

In Quang Tri, our company occupied a portion of an uncompleted

children’s hospital, not bad quarters considering that those who came

after us had to live in tents. Or worse: officers of the 71st AHC, a

sister company, lived in converted dog kennels.

On January 30, the 1st Brigade, US 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized)

began clearing Route 9 up to the Laotian border. Khe Sanh, the former

Marine base besieged during the Tet Offensive in 1968, was reopened on

January 31. On February 8, the first ARVN troops were air assaulted on

US helicopters into Laos. Lam Son 719 had begun in earnest.

As company Executive Officer, I did not fly on a regular basis. Maj.

Searcy, our Commanding Officer, liked to fly and, perceiving some

untapped administrative talent in me, made me XO -- a position normally

filled by a captain -- when I was still a 1Lt. None of the current

captains in the company felt slighted by this choice (they wanted to

fly, too) so I busied myself with the task of looking busy. Fortunately,

I had a good 1st Sgt. who assumed much of the paper-pushing tedium.

Shortly after we arrived in Quang Tri, I made captain and convinced Maj.

Searcy that I‘d had enough of being XO and surrendered my desk to a

recently arrived, second-tour captain who, wisely, saw that sitting

behind one could be a life preserving tactic.

I went back into Flight Operations where I had worked the previous

summer and considered myself to be on the sidelines of Lam Son 719.

Operations officers did not fly much, either. Since I was due to go back

to the states at the end of April, and it was clear that the operation

we were participating in was dangerous and sometimes deadly, I was not

unhappy with this assignment.

Nevertheless, as activity in Laos increased and demanded more and more

aviation support, I found myself flying again, primarily on resupply

missions to US troops in the field in the vicinity of Khe Sanh.

So, on March 3, my crew – 1Lt Flemer, pilot; SP4 Rhodes, crew chief; and

SP4 Padilla, door gunner – and I were resupplying troops on a rolling,

upland plateau known as the "Punch Bowl" to the northeast of Khe Sanh.

Sometime late that morning we got a call to report to the laager pad at

Khe Sanh for a new mission. We would be flying into Laos to insert ARVN

troops into an LZ known as Lo Lo (named for Gina Lollobrigida) where

that morning seven helicopters were hit by intense ground fire and five

shot down in the LZ. This hair-raising fact was not included in the

hasty briefing we received prior to departing for Laos.

Enroute to the pickup zone in Laos, we encountered some air bursts at

4,000 feet from anti-aircraft fire. The pickup was uneventful, although

maintaining visual contact with the flight was difficult because of much

smoke and haze.

The Air Mission Commander (AMC) was Red Oak Dragon, and his

responsibility was to mark the LZ with a smoke grenade. I spotted yellow

smoke in a cleared area ahead and identified it as "mellow yellow" which

the AMC verified and set up for my approach. Everything was fine until

we were on short final about two hundred feet above the ground when we

came under intense small arms fire from the right side of the aircraft.

I think I tried to nose the aircraft over and pull pitch to fly out, but

there was no power. Luckily for us, we were close enough to the ground

to make a controlled crash into the LZ. I don’t remember making a call

or saying anything to the crew over the intercom. We were all out of the

helicopter within seconds of hitting the ground, too fast for me to

think to retrieve my survival vest with radio and flares or my .45 on my

web belt, both hanging from my seat.

Somehow, I linked up with my crew chief, Rhodes, and we cautiously moved

away from the burning helicopter, staying low to avoid the M-60 machine

gun ammo that was cooking off in the fire and exploding willy-nilly. Lt.

Flemer and the ARVNs, unbeknownst to us at the time, bolted from the LZ

and would be picked up the next day. My door gunner, Gary Padilla, was hit by

enemy fire on the way in and killed, also, unknown to us at that time.

Rhodes and I were immediately aware of the many dug out fighting

positions that surrounded the LZ on its southern side, the direction in

which we were moving. Fortunately, they were empty. It did not mean,

though, that there weren’t more bad guys within reach of us, and it

seemed prudent to make small movements and then listen to determine if

we had been detected.

Rhodes and I were immediately aware of the many dug out fighting

positions that surrounded the LZ on its southern side, the direction in

which we were moving. Fortunately, they were empty. It did not mean,

though, that there weren’t more bad guys within reach of us, and it

seemed prudent to make small movements and then listen to determine if

we had been detected.

Later, we would learn that two Shark gunships were shot down when they

nosed around our ambush site. All crewmembers were successfully

extracted.

We made our way to a bomb crater about 20 to 30 feet across. Above us

was an Army O-1 spotter plane. I’m sure he was there because of our

predicament. He was flying in tight circles over our heads. I got into

the middle of the crater and tried to signal him. I have no idea if he

saw me or not, but I can distinctly remember hearing enemy rounds

hitting the skin of the Bird Dog, eventually driving him away. With no

radio, no way of telling anyone we were alive, we were listed as missing

in action on the 101st Aviation Group’s log of the day’s activities.

We went down late on the afternoon of the 3rd, a Wednesday as I recall,

and would not get out until Saturday morning, the 6th. We found a thick

clump of low, scrubby bushes that seemed to provide excellent

concealment and made that our home for the next two and half days. Time

seemed to stop, and we rotated through daylight and darkness, feeling

fairly secure when it became apparent that the bad guys were going to

leave us alone. The only excitement came when a Cobra gunship just to

the east of us fired rockets at such a high elevation that the rocket

motors burned out and detached before reaching the target and several

crashed through the brush near us

We smoked our last cigarettes, slept on and off, and prayed that it

would rain.

We had no water other than the dew that would form overnight on the

leaves of our hideout. It was just enough to keep us from becoming

parched to the point of not being able to speak.

It was thirst that finally drove us from our shelter Saturday morning.

We could hear voices to the southwest of us, and we moved in that

direction. We could see troops moving back and forth on a low ridgeline

ahead of us, but we couldn’t tell at first if they were friend or foe.

When we could make out that the troops were wearing the distinctive G.I.

steel pot, we felt safe to make our move and approached with hands

raised saying something like "G.I., don’t shoot."

They were glad to see us, and shared what water they could spare. I

approached a South Vietnamese soldier who appeared to be the radioman

and asked to use his radio. I dialed in the FM frequency we had been

using the day we went down and immediately made contact with Red Oak

Dragon. I told him who we were, and within minutes, it seems, a Dustoff

helicopter was clattering into our LZ. The ARVN commander insisted that

his dead troops in body bags be loaded first, but the Dustoff pilot

would have none of that. He had his crew chief step down and bar their

way, and we hopped aboard. Back at Khe Sanh, we had to scurry into the

first available bunker because the airfield was under rocket attack.

We soon learned about Butch and his crew going down on the 5th two days

after us. They were still on the ground in Laos but in radio contact.

Their plight made our scrape sound like an unscheduled R&R.

I’ll let Butch tell you about it in an abbreviated version of his

account that appears on the 174th web site:

We were just west of A Luoi when we were hit by .51 cal fire. At least

one round hit the engine, and it quit. I got off a MAYDAY call…I

executed a low-level crash landing into the trees, letting the tail boom

take the brunt of the crash. No one was hurt. Everyone got out without

trouble…We only had one survival radio, our individual weapons, and our

individual canteens. There was no food on the ship….

We saw some NVA coming toward us, so we moved off about 200 yards. We

knew the NVA would have no trouble finding our ship, so there was no

point in staying near it…. We came to an abandoned NVA .51 cal pit that

we thought we could defend, and we set up there….

That evening we received a pretty serious ground probe from the NVA,

that in retrospect was probably intended for us to use up our ammo. My

most vivid memory of that evening is the "pop" sound of the spoon on a

grenade flying toward us, then bouncing off the trunk of a tree in front

of us, and exploding on the other side of the tree.

Thank God for the US Air Force AC-130A "Spectre" gunships. They were

night vision equipped and would fire within 20 to 30 FEET of our

position. The NVA quickly learned that any serious threat against us was

quickly met with an air strike during daylight hours and Specter during

the night….

The USAF FAC (Forward Air Controller) reported that, at one time, he had

eight sets of bombers stacked up waiting to put their loads in around

us. Only once did they scare us. When the FAC talked to his jets, he

would have to tune his radio to their frequency and couldn't talk to us.

A Thai team put a load of CBU (cluster bomb units) in very close, and we

couldn't tell him just how close it was. Our gunner was hit in the arm

from some of the shrapnel.

BG Sid Berry flew over us that morning and said they had a plan for "one

more thing" to get us out, but after that we were on our own. Naturally,

we understood there is only so much anyone can do, but those were pretty

scary words. For security reasons he didn't tell us what they planned to

do. It involved inserting (a) Hac Bao company about a mile southeast of

us that afternoon. The Hac Bao were the Black Tiger troops of the 1st

ARVN Inf Div that would recover downed US crews in Laos.

We weren't exactly sure what was going on at first. Then we could see

what was obviously a combat insertion, and listened to almost continual

fire fights as the ARVN worked their way to us….

I don't remember sleeping at all during those three days and two nights.

We were very much aware that the Hac Bao were getting close to us. We

could talk to the FAC and he had a Vietnamese "backseater" who could

talk to the Hac Bao. We had arranged a password--we were to call out

"Witch Doctor" and they "Hac Bao." But they kept saying "A OK." We'd

tell the FAC that they were not saying the correct words and to have his

"backseater" get it right, but this never happened. It really didn't

matter much, for we only had four rounds of ammo left when they got near

us. If it hadn’t have been them, we would have had to go with whoever it

was anyway….

We linked up about 3 p.m. and moved back over the same terrain and

trails they had taken to get to us. It took us about 3 hours. We passed

concrete bunkers and some impressive NVA works. It was obvious that the

NVA had "built to stay" in this area. (The Hac Bao) were very good

troops and certainly had our respect and appreciation—they saved our

lives!

You’d have to know Butch to appreciate what he did upon landing at Khe

Sanh after being picked up on March 7th. Forthright and plainspoken,

prone to do or say the first thing that comes to mind, Butch acted on

instinct and reflected later. As they got off the helicopter at Khe

Sanh, he remembered with distinctly less equanimity what BG Berry had

said to them, that if the Hac Bau insertion did not work, no more Army

resources would be "wasted" to get them out and they would be on their

own. As Berry and General Creighton Abrams, Westmoreland’s successor as

Commander of all US forces in Vietnam, extended their hands in welcome,

Butch ignored Berry, refusing to shake his hand, and grasped Abrams’

hand in both of his.

While on the ground in Laos, Butch was promoted to captain by our new

CO, Maj. Dale Spratt the same day Berry made his statement. Butch

recalls in a private monograph he published in 1995 about his experience

that he requested over the radio that Berry be sent down to pin on his

new rank, an intended sarcasm since it was rumored that Berry never flew

below 7,500 feet. Butch retired in 1991 with the rank of major after

more than 20 years of service.

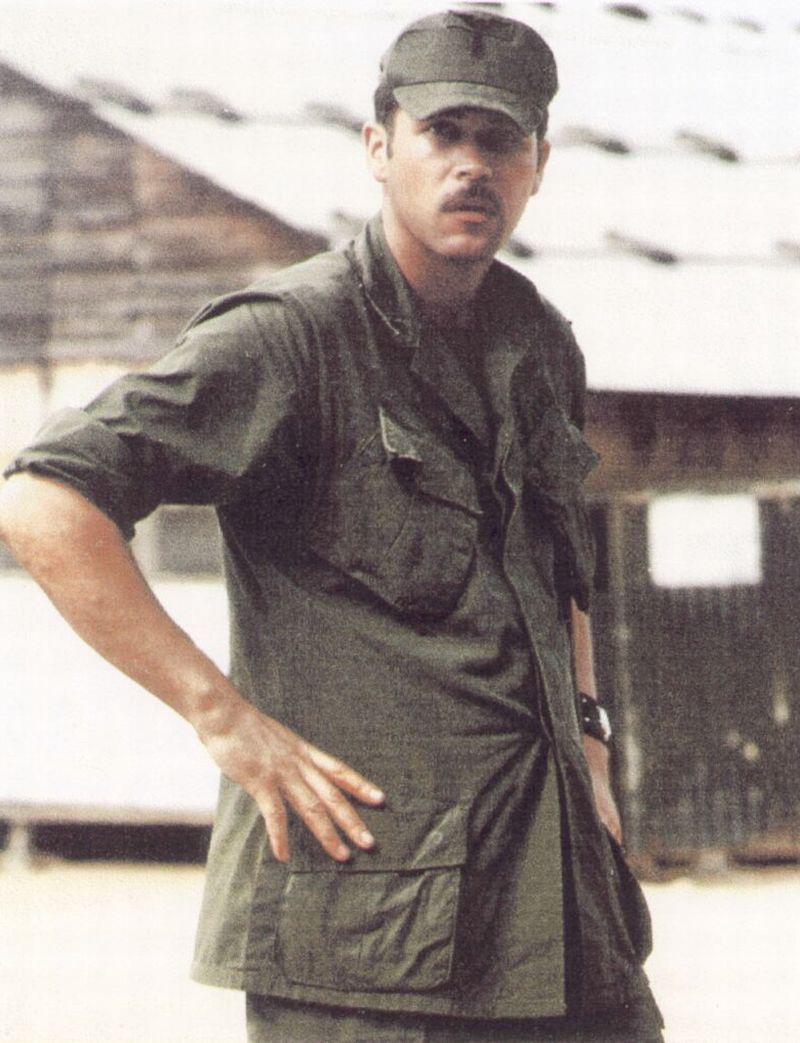

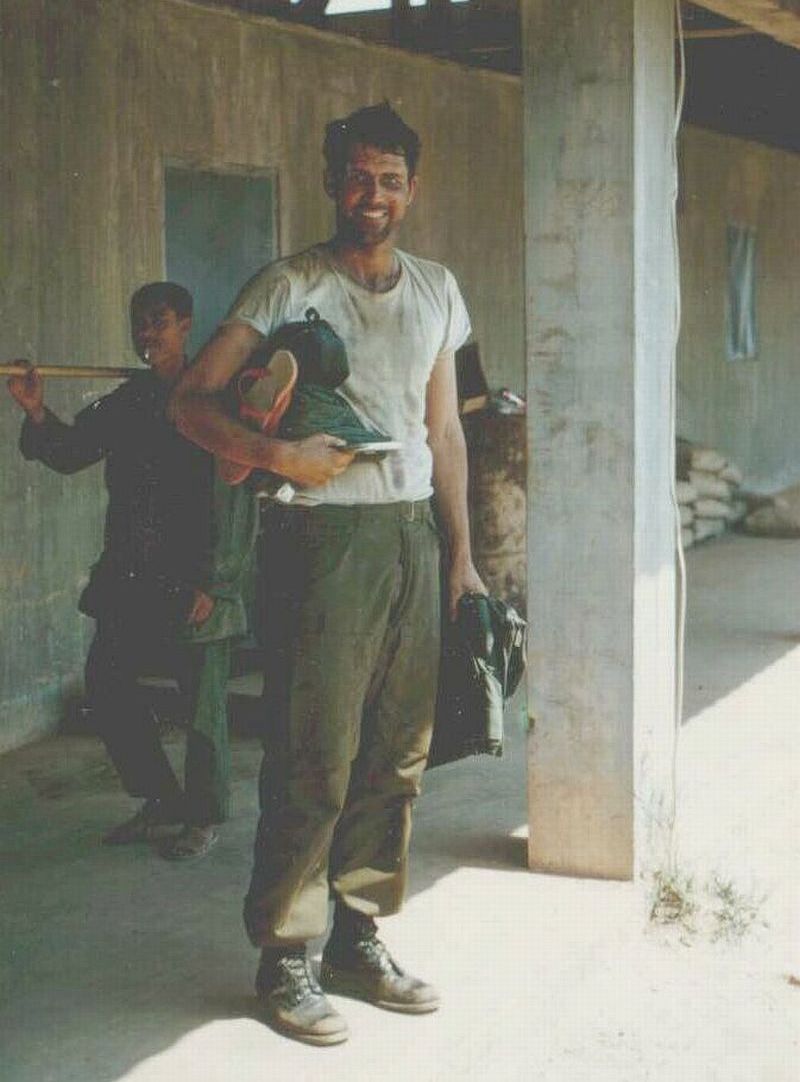

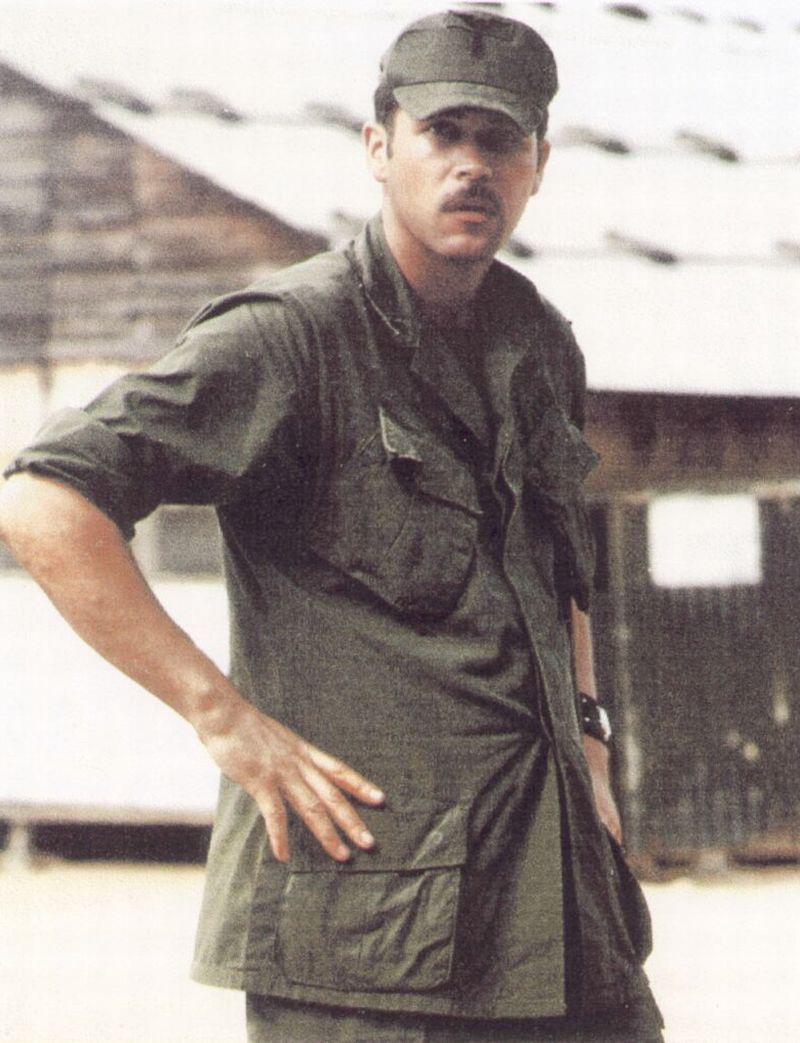

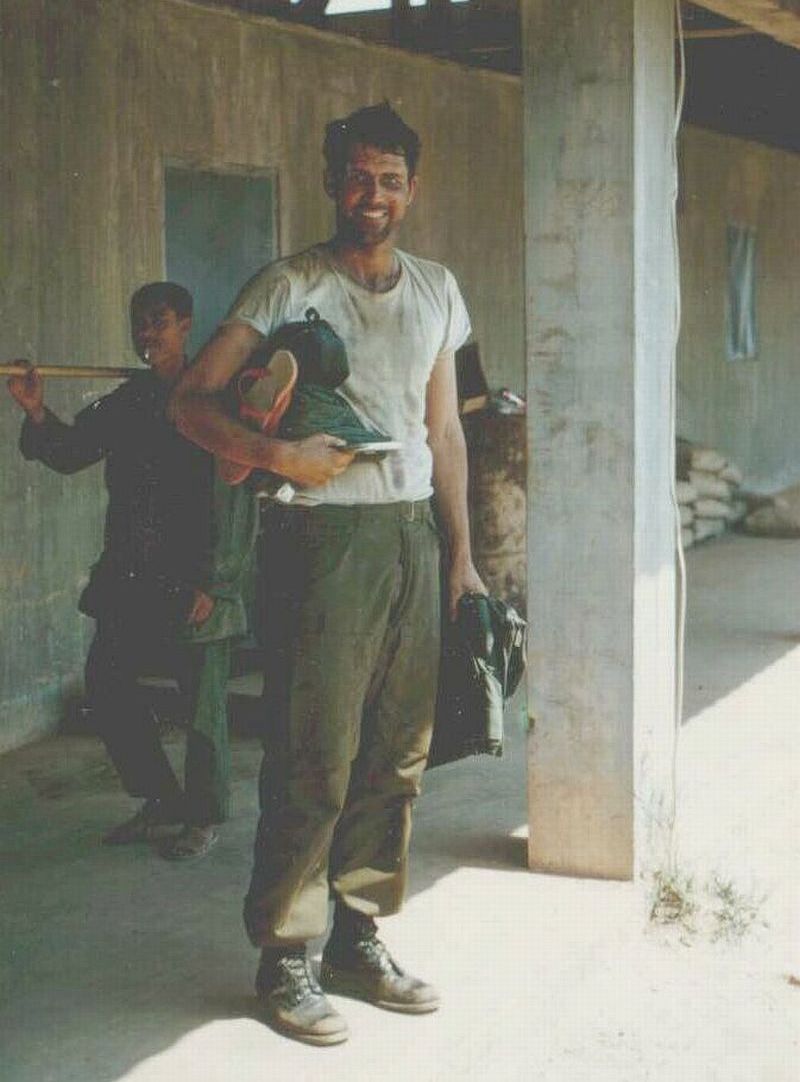

Above Left: John Bishop before "shoot down." Right: John Bishop after "recovery." Photos courtesy of "the late" Shark 7 Fred Thompson

Back in Quang Tri, after I’d showered and put on clean fatigues, I was

told that John Rich, an NBC news correspondent, wanted to interview me

about our shoot down. (photo by Fred Thompson below).

(Voice of John Chancellor, NBC News): "And it remains out of reach of

the South Vietnamese. But it was disclosed today that Laotian troops and

some irregulars are advancing on the road from the west And as our

correspondents there are learning, the part of Laos occupied by the

South Vietnamese, is still these days a very dangerous place."

(Voice of John Bishop): "This was the first lift I made into what I

assumed was the correct LZ. I had seven ARVNs on board and I don’t know

what happened to them after landing. All I remember is getting out of

the aircraft. I don’t remember seeing any of the troops or any of my

crew until I finally linked up with my crew chief and we evaded and

escaped the enemy.

The only thing we really had to subsist on was the moisture on the

leaves in the morning, the dew, that had formed and we sucked leaves and

this helped to alleviate some of the thirst.

This morning we figured, well, it doesn’t appear that anybody really

knows where we are. Of course, I didn’t have my survival radio so we

moved out this morning and were very fortunate striking on to an ARVN

unit located 700 meters further to the southwest. We linked up with them

and we coordinated Dustoff and lifted out of their LZ about 10:00 or

11:00 o’clock this morning."

(Voice of John Chancellor): "A South Vietnamese officer is quoted today

by the Associated Press as saying there now between 20 and 24,000 South

Vietnamese troops in Laos. In addition to that force, the South

Vietnamese have 23,000 troops in Cambodia which means that in South

Vietnam itself there are practically no first line South Vietnamese

troops left, only elements of one Marine division."

I never flew again after my shoot down. In about two weeks, I developed

a high fever and bone rattling chills. Malaria! Just that brief time on

the ground in Laos without the daily anti-malarial dosage was enough to

make me vulnerable to a mosquito bite.

After several days in the infirmary in Quang Tri, I was shipped south to

a hospital in Quin Nhon with a diagnosis of falciparum malaria, the

worst kind. From there, I was med-evaced through Tokyo, Japan and on to

Valley Forge Military Hospital. I spent a couple of nights there, was

discharged and went home to see my family in southeastern PA. Within

days, I was back in Savannah, and on April 5, 1971, married my wife,

Patricia. I’d been out of Vietnam about two weeks and ended my year-long

tour about a month and a half short.

What can I say about Vietnam? It was exciting. It was challenging to

become a good pilot and, ultimately, an aircraft commander. You worked

hard to build on the basics learned in flight school; you learned how to

land to a pinnacle with shifting, deceptive winds or how to nurse a weak

ship off the ground with a maximum load and high density altitude; you

learned sling loads, you flew night flare missions, you flew in bad

weather, you flew twelve- and thirteen-hour days, and, sometimes, but

not very often, you got shot at.

I remember my first combat assault in Vietnam. I was flying in flight

lead with Lt. Bill Smith, a laconic Yankee from Massachusetts. Not only

was he the flight leader but he was talking on at least three different

radio frequencies, giving instructions to our crewchief and gunner over

the intercom, maintaining order within the flight, briefing various

ground commanders, getting artillery clearance and all the while

patiently explaining to me why this and why that. I was deeply impressed

and greatly dispirited. It wasn't possible to learn how to do that in

one year. Surely, this guy was on his third consecutive tour and had

logged thousands of hours in the air doing the impossible everyday.

But you learned how and it became almost second nature. You were proud

to do your job well. With your hands on the flight controls and your

feet on the pedals, you and the helicopter became one mechanism: flesh,

blood, and bone fusing into steel control tube, life and energy

pulsating through control linkages and hydraulic lines and all of it

sheathed in an olive drab skin of magnesium alloy.

Unfortunately, good pilot technique was about all we brought with us to

Lam Son 719. None of us had flown in a truly hostile environment before,

and to make matters worse, the Army did not heed the warnings of the 7th

Air Force about the concentration of antiaircraft guns – 57-, 37-, and

23mm – and small arms in Laos. Up until that fateful day of March 3, the

US Army and the ARVN tended to "go it alone" without fully utilizing the

tactical air support available to them. They preferred to make

insertions as soon after first light as possible to give the troops

maximum time to prepare night defensive positions. Early morning cloud

cover often made it impossible for strike aircraft to provide support.

The resources at our disposal were awesome: Air Force F-4 Phantoms out

of Phu Cat, Da Nang, and Thailand; F-100 Super Sabres from Phan Rang;

Marine and Navy F-4s, A-4 Skyhawks, and A-6 Intruders; AC 119K Stinger

and AC-130A Specter gunships; B-52s out of Thailand; A-1 Skyraiders for

search and rescue; and Vietnamese Air Force assets, including

helicopters and strike aircraft.

Most of the close air support was provided by F-4s and F-100s delivering

500-pound Snakeye bombs and napalm at a low angle. Laser-guided bombs

(the precursors to today’s "smart bombs") were used effectively against

enemy gun emplacements and armor.

During daylight hours, a new pair of strike aircraft would appear on

station every 10 minutes, and six FACs flying OV-10 Broncos provided

traffic control and identified targets. Support was around the clock and

only lapsed when weather conditions prohibited it.

This mighty air arsenal, even when used to maximum effect, could not

give the ARVN the edge it needed for a successful campaign. The NVA knew

we were coming, perhaps two months in advance, and prepared accordingly.

In the dense, mountainous terrain, there were few sites suitable for

LZs. The NVA "triangulated these areas and much of the high ground with

antiaircraft weapons and preregistered their artillery and mortars to

zero in on the potential LZs." They knew the terrain and moved freely

through its dense vegetation, making them hard to spot. Weapons

emplacements were well camouflaged. It is estimated that among the

approximately 35,000 NVA troops opposed against us in Laos, there were

nineteen NVA antiaircraft battalions.

The ARVN, on the other hand, tended not to move very far from their fire

bases, which permitted the NVA to "hug" the perimeter in offensive

positions and unleash a withering barrage of small arms fire on

helicopters attempting to land or take off. Their proximity to the ARVN

made it dangerous to call in air strikes. (One ARVN commander actually

called in a strike on his position when he realized the NVA were digging

through his bunker.)

All this, of course, reduced the mobility of the ARVN troops and made it

difficult, if not impossible at times, to resupply them. Beginning on

March 18, General Lam, with President Thieu’s blessing, began

withdrawing troops from Laos almost a month and a half ahead of

schedule. As the ARVNs prepared to vacate their fire bases and move

their tanks and vehicles east along Rt. 9, the NVA began massing their

Soviet-built tanks to pounce on the retreating column. If it had not

been for tactical air support which, all told, knocked out 108 of the

estimated 120 enemy tanks, the South Vietnamese would have suffered

grave losses. Incidentally, Cobra gunships were credited with six tank

kills during Lam Son 719.

About the best that can be said of Lam Son 719 was that it probably

interrupted NVA movement enough to prevent a major offensive in South

Vietnam during the spring of 1971.

Lam Son 719 was a major effort to "Vietnamize" the war, to let ARVN

soldiers fight and die so that American soldiers could live and go home.

The South Vietnamese suffered a 50% casualty rate during Lam Son 719.

U.S. losses were 137, almost all aircrewmembers. Five strike aircraft

were shot down and 90 helicopters were lost. Fourteen of our company’s

20 UH-1H Dolphin helicopters and all six of the UH-1C Shark gunships

were lost during the operation.

The two worst days to be flying in Laos were March 3rd when eleven Hueys

were downed in the vicinity of LZ Lo Lo and March 20th when ten Hueys

were shot down attempting to extract ARVN troops from PZ Brown.

In mid-March, Newsweek had a cover story on the "helicopter war" and

didn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know but made it clear to the

outside world what a dangerous business this was.

I

don’t know anybody who went to Vietnam to win the war. Ultimately, it

was a matter of survival, of doing your time and getting back home. I

don’t remember ever having a conversation about the "rightness" or the

"wrongness" of the war while I was there. It would have made no sense.

"It don’t mean nothing" was the classic retort that minimized a serious

situation without making trivializing it. The zealots were back in

Washington or were REMFS (Rear Echelon Mother F**kers) who got no closer

to actual combat than falling down drunk in the Officers’ Club. Zeal

under fire would probably get you killed.

The war, after all, was unwinnable. Before the end of the dry season

that May, enemy truck traffic within Laos reached a peak for the year,

surpassing that for a similar period one year before. Nothing we did

seemed to make a difference in the North Vietnamese will to fight on.

What we failed to realize was that they were the only ones fighting for

something they believed in: the reunification of Vietnam under their

control.

Our involvement in Vietnam went back to the end of WW II when we helped

restore the French to colonial rule in Indochina. Sadly, we learned

nothing from the French experience. By the time Dien Bien Phu fell in

1954, we were subsidizing 80% of the French war effort. Entreaties to

avoid getting involved in a land war in Asia were falling on deaf ears.

Cold War hysteria, beginning with the fall of China to Communism in 1949

and followed quickly by Russia’s successful explosion of an atomic bomb,

reached a giddy level of paranoia with Senator Joseph McCarthy’s

Communist witch hunt in the early 1950s. The coldest warrior of them

all, John Foster Dulles, beat the drum at the State Department long and

loud enough until it was accepted as fact that Communism was a unified,

worldwide conspiracy, and that Asian dominoes were to be propped up at

all costs.

Our inevitable intervention in Vietnam with the introduction of US Army

advisors in 1955 began as a matter of national security. Kennedy

inherited Eisenhower’s commitment but seemed ambivalent about how far we

should be drawn in. Had he lived, he may have de-escalated the

commitment after the 1964 election, but that’s merely speculation. Under

Johnson and Nixon, it became a matter of national prestige to continue a

war that was becoming increasingly unpopular, and, after the Tet

Offensive in 1968, clearly beyond our ability to bring to a successful

conclusion. The mantra now became "Peace with honor", a Nixonian conceit

for saving national face or, more likely, his own.

Having ignored or spurned numerous attempts by allies to broker a

negotiated settlement to the war, we finally sold out our South

Vietnamese allies in 1973 in Paris with a treaty that differed little on

paper from the Geneva settlement of 1954. In other words, "the new

political order was approximately what it would have been if America had

never intervened" to quote Barbara Tuchman in her essay "America Betrays

Herself in Vietnam" from her 1984 book The March of Folly.

If any shame attaches to our involvement, it may be in the fact that the

burden of fighting and dying fell disproportionately on draftees who had

no choice about it. Young men with deferments could listen to Country

Joe and the Fish sing the "I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die-Rag" and

appreciate the irony in the lyric "…put down your books, pick up a gun,

we’re gonna have a whole lot of fun." They held tightly to their books.

The inequity was not lost on the less privileged whose own anthems

ranged from the urgency of the Animals’ "We Gotta Get Out of This Place"

to the unambiguous cynicism of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s

"Fortunate Son": "…It ain’t me, it ain’t me, I ain’t no senator’s

son."

I had a choice, but I chose to go. I have no regrets about serving in

Vietnam. It has proved to be neither an advantage nor a disadvantage.

There are no nightmares, no physical or psychic wounds. There has been a

kind of closure to the whole thing. I have seen some of the men with

whom I served on two occasions during annual reunions of the Vietnam

Helicopter Pilots Association: in Ft. Worth in 1988 and in Atlanta in

1992. Those reunions were opportunities to observe that most of us

picked up and moved on with our lives.

Vietnam: it was just something we did once upon a time.

I would like to acknowledge the help of Mike Sloniker, the Historian of

the 174th web site, who provided me with a number of fascinating

documents, some previously classified, that gave me a greater

understanding and appreciation of the scope of Lam Son 719. Mike joined

the 174th in Vietnam in July 1971 after I had left so our paths did not

cross there.

I’d also like to recognize Fred Thompson. Fred and I served together.

Fred was a Shark gunship pilot during Lam Son 719 and was shot in the

head on February 24, 1971 while on a mission in Laos. Fred’s efforts to

locate former members of the 174th have been singular and untiring. Fred

provided me with the audiocassette with Butch Elliott’s "Mayday." It’s

an amazing record of much of the action of March 5, 1971 and gives me

chills every time I listen to it.

Thanks, Fred and thanks, Mike.

|

Click here

Click here  to e-mail us at the website

to e-mail us at the website

![]() Return to top of: 1971 History Page.

Return to top of: 1971 History Page.![]() Return to top of: Home Page.

Return to top of: Home Page.

Rhodes and I were immediately aware of the many dug out fighting

positions that surrounded the LZ on its southern side, the direction in

which we were moving. Fortunately, they were empty. It did not mean,

though, that there weren’t more bad guys within reach of us, and it

seemed prudent to make small movements and then listen to determine if

we had been detected.

Rhodes and I were immediately aware of the many dug out fighting

positions that surrounded the LZ on its southern side, the direction in

which we were moving. Fortunately, they were empty. It did not mean,

though, that there weren’t more bad guys within reach of us, and it

seemed prudent to make small movements and then listen to determine if

we had been detected.